This is one of an occasional series. Some of the newspaper columns by Arch Merrill never made it to his series of books. This column talks about the early days of Bausch & Lomb and also brief mentions of the founding of other Rochester factories.

When $32 Rent Worried Bausch

That Was 102 Years Ago — Landlord Reynolds Held Lease on Shop

By Arch Merrill

Originally published: Nov. 16, 1958

SOMETIMES rare objects turn up at housecleaning time.

SOMETIMES rare objects turn up at housecleaning time.

The other day the vault at the main office of the Bausch & Lomb Optical Co. yielded a 102-year-old document which illustrated an ancient axiom: “Tall oaks from tiny acorns grow.”

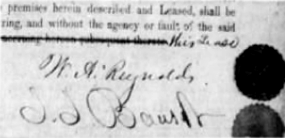

The paper is a lease executed Oct. 20, 1856 between William A. Reynolds, lessor, and J. J. Bausch, lessee, covering “the tenement in the Arcade Building known as No. 20.” The lease was for three years and five months and Bausch was to pay $30 a month for the first five months and $32 a month for the remainder.

Bausch agreed to use the premises “himself as an optician” and the owner of the old Reynolds Arcade, predecessor of the present Main Street building, pledged himself not to lease to any other optician the Room 5 previously occupied by Bausch.

William A. Reynolds, who made out the lease and signed it in a precise small hand, was the son of the builder of the Arcade. John Jacob Bausch, co-founder of one of Rochester’s major industries, then a struggling artisan, wrote his name in a bold hand.

The Room No. 5 referred to In the lease, first occupied by Bausch in 1853, was the tiny acorn from which sprang the tall oak that is the world famous optical plant which sprawls along the Genesee..

* * *

HISTORIC LEASE — Vault in Bausch & Lomb Optical Co. gave up this document which was lease of quarters in old Reynolds Arcade Building by J. J. Bausch (note correction on spelling), founder of optical firm. As shown, lease was executed Oct. 20, 1856.

JOHN JACOB BAUSCH came to this country from his native Germany in 1849 at the age of 19. He had mastered two trades in the Fatherland, that of wood carver and lens grinder.

For three years he worked as a wood carver in Buffalo and in Rochester, both booming young canal ports in those days.

The loss of two fingers in a buzz saw compelled young Bausch to turn to his other trade, that of optician. In 1853 he opened the little optical shop on the balcony of the Arcade, where he made spectacles by hand.

A fellow countryman, Henry Lomb, a young cabinetmaker, invested $60 in the enterprise. Later Lomb became Bausch’s partner, taking care of the sales end while his partner ran the shop. Bausch perfected a lens grinding machine, one of the first in America, and the partnership gradually grew and prospered.

But those early years in the 1850s were struggling ones, as Bausch’s accounts with Landlord Reynolds, which also turned up in the vault, reveal.

Sometimes it was difficult for J.J. Bausch to meet even the $32 monthly rent. Never was the sum paid in advance as the lease stipulated. The rent for October, 1857, was paid in two installments, $20 on Nov. 14 and the $12 balance four days later. Bausch gave his note for $198 in paying his rent for the final six months of the lease.

The B. & L. housecleaning job also brought to light a later lease, one of April 29, 1863, whereby John J. Bausch & Co. took over “the small room; about 15 feet deep which is taken off from the room rented to George Smith on North Water Street.” The annual rent for this additional space after the shop had moved to a new location was $80.

And during the Civil War when incomes were taxed for the first time, another document reveals that Bausch & Lomb paid to the government as its “duty or tax on income” for the year 1862 the sum of $7.92

* * *

OTHER MIGHTY Industrial oaks of Rochester sprouted from small seeds.

The Eastman Kodak Co. began with a young bank clerk’s experiments with photographic emulsions in the kitchen sink of his widowed mother’s home.

Two young men, Kendall and Taylor, rented a shop, began making thermometers and when their wares filled a truck, went out on the road and sold them. That was the beginning of the Taylor Instrument Companies.

William Gleason started in a little machine shop in which he did all the designing himself.

The Todd Co., now a division of Burroughs Corp., originated with two Todd brothers fashioning a check protector in a Gregory Street wood shed.

Frank Ritter was making furniture in a small shop before somebody asked him to make a dental chair. The big Ritter Co. plant on the West Side is the result.

Delco Division of General Motors, formerly the North East Electric Co., began with Edward A. Halbleib’s little coil shop in a Water Street basement.

While he was working his way through college, Rae Hickok baked the enamel for watch fobs which he sold to fellow students. That was the start of the Hickok Belt industry.

A woman named Baker in 1840 began making boys’ trousers in a tiny shop on Front Street—-for 25 cents a pair. Thus began Rochester’s far-famed clothing Industry.

From a small Rochester plant where it made steam pressure cookers, the Wilmot Castle Co. has grown in 75 years to become a leading producer of sterilizers and hospital operating room equipment.

* * *

AND WHILE we are on the subject of oaks, I received a little book entitled “The Corners.” It is a history of the community of Oaks Corners in the Town of Phelps, Ontario County. Oaks Corners is not a very large place but it has a long and interesting history and author Mabel E. Oaks (Mrs. Nathan Oaks 3d) tells it well.

As you may have suspected by this time, the village was not named because of its oak trees, but because of a pioneer family named Oaks. Its first settler was Jonathan Oaks, who came from Massachusetts in 1790 and built a log house.

This book is not merely a compilation of names, dates and statistics, although, the important dates and names are there. It tells of the customs of pioneer and later times, what the settlers wore, what they ate and drank, how they lived

It tells of the coming of the railroad, the Auburn Line; of the development of the sand and quarry business that is still its leading industry; of hop growing, of maple sugaring and ice harvests of yesteryear.

This paragraph at the conclusion of the book imparts its flavor:

“‘Oaks Corners’ brave beginning in the wilderness of Western New York is an integral part of its story. This book, in the main, tells of people and times that are gone. Some day our village, too, may disappear. Life at the Corners, perhaps unimportant in itself, has been representative of many New York State hamlets.”